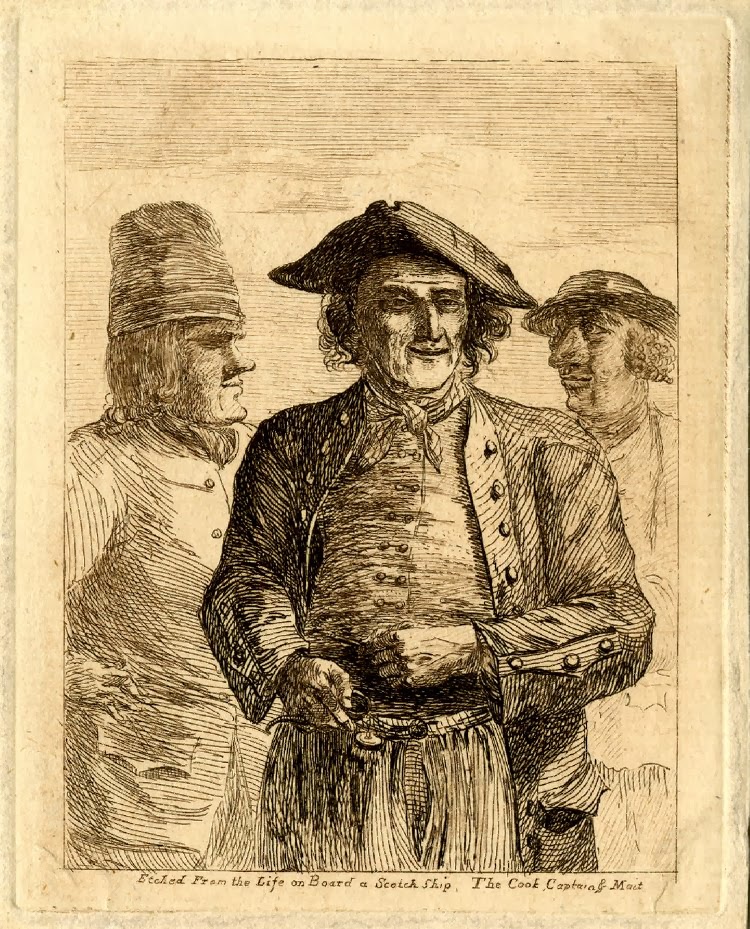

‘From Ushant to Scilly ‘tis thirty-five leagues’: Some musings on sailing directions

With all the fascinating new developments going on in

eighteenth-century navigation, it is easy to forget that it was not all

sextants and chronometers. Even the best instruments and new techniques, even

in the hands of the most experienced and skilled navigators, reached the limits

of their usefulness once a ship was in coastal waters, which means that a

considerable part of eighteenth-century navigation is actually better described

as good old-fashioned pilotage. Pilotage demanded completely different skills

and equipment of the practitioner than blue-water navigation: in coastal waters,

what served a navigator better than any new-fangled instruments were a sounding

lead, a good memory and a sharp-sighted lookout, as well as, of course, sailing

directions.

|

| Detail from "Earl of Cornwallis Bound to Bengal," William Gibson, 1783 Courtesy of The Mariners' Museum and Park, Newport News, VA. |

Sailing directions have something decidedly ‘low-tech’

about them. The earliest written ones I have seen were used by ships of the

Hanseatic League in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but they are almost

certainly very much older. They are descriptions, either written down or

memorised, of distances, depths, landmarks and other topographical information

for particular waters or sailing routes. In other words, sailing directions

were pilots to take away and carry with you, even where live pilots might not

be easy to come by.

Sometimes, they were rhymed so as to make memorisation

easier. In fact, most people with an interest in maritime history or seafaring

in general will probably know at least one example, perhaps without even

realising: parts of the famous sea song Spanish

Ladies sound suspiciously like sailing directions. The second verse

contains something that is more or less a (somewhat abbreviated) manual of how

to proceed when entering the English Channel from the south before coming in

sight of land but suspecting that you are ‘in soundings’:

We hove our ship to, with the wind from sou'west, boys

We hove our ship to, deep soundings to take;

‘Twas 45 fathom with a white sandy bottom

So we squared our main yard and up Channel did make.

In the third verse, the most important landmarks –

such as prominent headlands and lighthouses – that a ship sailing up the

Channel will pass are listed:

The first land we sighted it was called the Dodman

Next Rame Head off Plymouth, Start, Portland and Wight

We sailed by Beachy by Fairlight and Dungeness

And then we bore up for the South Foreland Light.

|

| Detail of South Foreland Light from "A Packet Boat Under Sail in a Breeze off the South Foreland," Thomas Luny, 1780, Yale Center for British Art. |

I don’t know if these were ever actually used as

sailing directions, or whether they mimic the real thing, but the detail given

in them, with its references not only to landmarks but also to depths,

composition of the sea floor, and hints at how to work the ship suggest that

they were.

One beautiful example that dates from around the

mid-eighteenth century is Wadhams

Directions, sailing directions from Cape Bonavista to the Wadham Islands.

It was famous among eighteenth-century navigators and I came across a copy in

the journal of John Dykes, master in the Royal Navy, who served with Edward

Pellew on the Newfoundland station in the 1780s.[1] The

directions open with the magnificent lines:

From Cape Bonavista to the stinking Isles,

The course is North full forty miles

Then you must steer away NE

Till Cape Freels Gull Isle bears WNW

Then NNW thirty-three miles

Three leagues off shore lays Wadhams Isles.

The rest is a more in-depth description comprising

another thirty-eight atrociously rhymed lines, but even though the poetic

quality might make philologists cringe, it certainly serves its purpose very

well; how well, you can tell from the fact that, while writing this, I cannot

help constantly reciting in my head “When within the channel you are shot/Three

fathom of water you have got/Port your helm and do take care/in the mid-channel

for to steer”. I think there is something touching in how the directions address

the navigator directly, like a trusty friend cautioning against narrow passages

and sunken rocks:

Therefore my friend I you advise

Since those rocks so dangerous lies

That you do never amongst them fall

But still endeavour to weather them all.

|

| Detail from "To the Survivors and Relations of the Unfortunate Persons who Perished in the Halsewell," P. Mercier, S.W. Forbes, and Rawlinson, 1786, National Maritime Museum. |

These sailing directions

had the reputation of being the best for the Newfoundland coast, and you can in

fact follow them easily on a chart (I have not so far had an opportunity of

running a field trial). Thus, despite their old-fashioned appearance, it is no

wonder that sailing directions in general remained in use alongside all

innovations in navigation, and are still in use today.

[1] Log of John Dykes, master,

HMS Winchelsea, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), Caird Library, LOG/N/W/1.