Today's guest post is written by Dr. Charles R. Foy. Dr. Foy is Associate Professor Early American & Atlantic History at Eastern Illinois University. His scholarship focuses on 18th century black maritime culture. A former fellow at the National Maritime Museum and Mystic Seaport, Dr. Foy has published more than a dozen articles on black mariners and is the creator of the Black Mariner Database

, a dataset of more than 27,000 18th century black Atlantic mariners. He is completing a book manuscript, Liberty’s Labyrinth: Freedom in the 18th Century Black Atlantic

, that details the nature of freedom in the 18th century through an analysis of the lives of black mariners.

Claim’d as a Slave: The Short Career of William Stephens in the Royal Navy

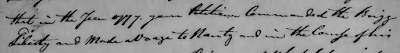

On December 8, 1758, Vice Admiral Francis Holburne, Port Admiral at the Portsmouth Naval Yard, notified the Admiralty he had 'inquired into the case of William Stephens on board his Majesty’s Ship the

Jason, who is claim’d as a Slave, the property of a Person in Maryland…'(Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Letter of Vice Admiral Francis Holburne, Dec. 8, 1758,

The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom (“TNA”), ADM 1/927. |

As naval regulations prohibited slave naval seamen, one might have assumed, as does

N.A.M. Rodger, that the navy was 'a little piece of British territory in which slavery was improper.'

[1] Thus, Stephens’ case raises questions as to slaves’ service in the Royal Navy, the scope of slavery in the British empire and the movement of Black seamen in the Atlantic. As I will detail below: Stephens’ Royal Navy service, while hardly commonplace, was not rare; the Royal Navy, while taking steps to keep slaves off its ships, also took measures that supported slavery; and Black seamen, both free and enslaved, moved about the Atlantic with regularity.

As is true with regards to most eighteenth century black mariners, we know very little about William Stephens. With the vast majority of Blacks of this time period being illiterate, there are few contemporaneous accounts of Black seamen’s lives.

[2] However, by utilizing the

Black Mariner Database ('BDM'), a dataset of information on than 27,000 black mariners and maritime fugitives, we can contextualize Stephens’ career to better understand his and other Black seamen’s maritime careers.

[3]

|

| Figure 2 HMS Jason Muster, 1758-59, TNA ADM 35/5889. |

Stephens voluntarily entered HMS

Jason at Portsmouth, England on October 27, 1758 (Figure 2) as an able bodied seaman. To be classified an able bodied seamen, Stephens would have had to been at sea for at least three years. According to the

Jason's captain, Stephens had gained his sea legs working as a slave 'in a Sloop coastways in America for five or six years.' Just how closely Stephens was questioned when he entered the

Jason about his maritime background or whether he was a slave is uncertain. What can be said is that a slave in the Americas working on a coastal sailing vessel for five years was not uncommon.

Olaudah Equiano’s time working on various ships between North America and the West Indies helped him purchase his freedom.

[4] Equiano and a considerable portion of the black population in England during the second half of the eighteenth century had been seamen in the Americas.

[5] Merchants in Rhode Island, New York, Virginia, South Carolina, and throughout the West Indies regularly employed enslaved Black seamen on their ships.

[6] In doing so, owners calculated that the wages and prize monies the men could earn would more than offset the risk owners might lose their property. Given the prevalence of this practice throughout the Western Atlantic, by both small slave owners and rich slave merchants, such as Henry Laurens and Aaron Lopez, it appears to have been generally profitable to send enslaved Blacks to sea.

How Stephens got to Portsmouth is unclear. Was he assisted, as had been Abraham Santvoord’s slave Tony, by a ship captain? In Tony’s case, the ship captain went so far as to transfer the runway onto a second ship at sea so the bondsman could get to England.

[7] However Stephens got to England, he hardly was the only slave from the Americas who reached England during the Seven Years War. Some, such as John Incobs, escaped their slave masters and appeared to have reached English soil by service on a ship. Others, such as

Olaudah Equiano and Emmanuel Carpenter, were brought to England by Royal Navy officers.

[8]

Two months after Stephens entered the

Jason his owner knew enough about the bondsman’s whereabouts to notify the Admiralty. Was his owner in England or did he learn of Stephens’ whereabouts through social or mercantile connections? We don’t know. But what is clear is the relative information imbalance between Stephens and his slave master. While his owner was able to find him more than 3,000 miles from Maryland, Stephens, despite being an experienced sailor, could not hide himself from his master. In the British empire, one’s former status as a slave left a person vulnerable to re-enslavement. Vice-Admiralty courts regularly presumed that Black seamen were slaves who could be sold as prize goods. This resulted in Patrick Dennis and considerable numbers of other captured free Black mariners being enslaved in the Americas.

[9] Admiral James Douglas, Commander of the Royal Navy’s Leeward fleet, purchased such captured enemy Black sailors for service on his private man of war.

[10]

Like John Incobs, who having fled his slave master found himself discharged in New York from the Royal Navy for 'being a slave,' Stephens and other former slaves could never feel completely safe from the Royal Navy returning them to their former masters. Even during the American Revolution, when the Royal Navy often proved to be a haven for runaways, those who fled to the Navy from Loyalist slave owners could find themselves 'returned to [their] owners.' Thus, in 1779, when HM Galley

Scourge docked at Port Royal, South Carolina, January, August, Ben and six other former slaves were discharged to the custody of their former owners. Similarly, in 1783 Dublin and four other Black seamen were discharged at St. Augustine from HM Galley

Arbutnot for 'being a Slave.'

[11] (Figure 3) In returning runaways to their former masters, the Royal Navy provided support to the institution of slavery.

|

| Figure 3 HM Galley Arbutnot Muster, 1783-1786, TNA ADM 36/10426. |

With an economy largely based on the cultivation and sale of agricultural commodities such as tobacco and wheat, the stereotypical image of slavery in the Chesapeake is of slaves using hoes to tend to such crops. And most slaves were so employed. But, as an insert in the 1775 Jeffreys map of Virginia and Maryland demonstrates, considerable numbers of enslaved peoples worked on the region’s wharves making hogsheads and loading the large barrels onto ships (Figure 4). Blacks, free and enslaved, also worked on a variety of vessels that moved such commodities to regional, continental and Atlantic markets. The

BMD contains data on more than 1,000 Black mariners from Virginia and Maryland. Advertisements for the sale of slaves who were 'used to the sea' or had worked as sailors were commonplace.

[12] Slaves were employed in the Chesapeake region as baymen, ferrymen, canoemen, seamen on ocean-going ships, and even as captains on small boats.

[13] During wartime, when maritime labor was particularly valued, scores of free blacks and enslaved individuals served on both British and American naval vessels. For example, when HM Galley

Cornwallis left Virginia for Charleston in 1780 among its forty seamen were Dick, Joe, Andrew, Ceaser, Thomas Cooper, Peter, and Hamden, slaves hired to the Royal Navy by Virginian Loyalist slave masters.

[14] Like William Stephens, these Chesapeake seamen ultimately did not have a choice as to whom they worked for. Whereas Stephens found himself returned from England to enslavement in Maryland, the seven Black seamen on the Cornwallis were instead sold as prize goods in Porto Rico.

|

| Figure 4 Jefferys 1775 Map of Virginia and Maryland |

The Chesapeake region, with its large bay, numerous rivers and regular influx of ocean-going vessels, offered enslaved individuals numerous opportunities for flight via the sea. The persistence and scale of maritime flight can be seen both in the regularity of fugitive slave advertisements for such runaways and the often futile efforts governmental authorities and slave masters made to stop maritime fugitives. During the eighteenth century there were not less than twelve hundred Chesapeake maritime fugitives.

[15] As did Stephens, these runaways sought to use maritime employment as a means to quickly put distance between themselves and their slave masters. The same year William Stephens was returned to slavery in Maryland, Tom escaped from Elk-Ridge Furnace. Described as 'formerly accustomed to go by Water' and having worked for a ship captain on the Chester River, the young slave was thought to have attempted to 'escape that Way,' i.e., by obtaining a ship berth.

[16]

When William Stephens fled his Maryland slave master he did not merely join a group of experienced Black seamen seeking to cross the Atlantic. At the same time, many Chesapeake runaways lacking maritime experience fought freedom via the sea. They included a Maryland runaway who in 1763 stole a canoe in an effort to seek freedom and Will Baker, who in 1762 sought to 'get on board some vessel that may want Men.' They and other maritime fugitives understood that canoes, small boats, skiffs and pettiaugers could serve as the first leg in a multi-legged maritime race to exceed their slave master’s grasp.

[17] Stealing such vessels also enabled new African slaves, whose their unfamiliarity with English made flight on land difficult, to more easily evade detection. Slave masters considered maritime fugitives 'cunning Rogue[s]' who could not be trusted.

[18]

The chaos of war provided the best opportunities for maritime flight. Being more concerned with a potential recruit’s muscle and expertise than his complexion or status as a bondsman, many commanders of merchant and naval ships willingly hired runaways. Often fugitives were employed as officer’s servants – the

BMD contains data on more than 100 Black servants on Royal Navy vessels. They include men such as Quashie Ferguson, who escaping his Rhode Island slave master, entered HMS

Rose as a Captain’s servant, and the unnamed negro servant of Captain Robert Jennys of HMS

Amity’s Assistance, who two years after Stephens was returned to enslavement, found the Royal Navy not to his liking and fled the

Amity’s Assistance.

[19]

In the face of maritime flight by slaves whites did not sit idly by. Government officials took steps to limit slaves’ access to shipping and to ensure that slaves 'largely stayed put.' Virginia and Maryland slave codes required slaves to carry passes when traveling off their master’s property. With slave masters receiving compensation for slaves convicted of criminal offences, violence as a tool to regulate slave behavior was central to eighteenth century justice in the Chesapeake. For example, in 1737 Maryland made it a capital offense for any person to aid in the stealing of 'any Ship, Sloop or other Vessel.'

[20] These official efforts were supplemented by searches of vessels and slave masters warning others not to 'harbor, conceal or employ' their runaway slaves. In attempting to ensure that ship masters and captains did not hire their runaways, Chesapeake slave masters regularly forewarned them 'from carrying them off at their peril.'

[21] Forty-four percent of fugitive slave advertisements for Chesapeake maritime fugitives contained such warnings. Thomas Reynolds and other slave owners requested that 'all Masters and Skippers to search their Vessels' for their bondsmen before they sailed.

[22] While the efficiency of such requests cannot be determined they appear to have had little effect. There are very few dispatches in colonial newspapers indicating either that a maritime fugitive was returned to his slave master or that a ship captain was prosecuted for carrying away, harboring or employing such a runaway. More common were dispatches about 'runaway negroes' being seen on ships at sea.

[23]

Stephens’ choice to flee to England needs to be understood within the context of the choices slaves had when running away. The primary attraction of maritime flight was it provided a quick means to flee and offered a reasonable possibility of permanent freedom, albeit, as noted above with a continual threat of re-enslavement. The attractiveness of maritime flight was hardly limited to those seeking to escape enslavement in the Chesapeake. The

BMD contains more than 5,000 maritime fugitives from throughout the Americas.

[24] In fleeing to England Stephens and other maritime fugitives found a respite from the threat of re-enslavement that continually threatened sailors of African ancestry in the Western Atlantic. The boast of white seamen that 'they would make their Fortunes' by selling fugitives who during the Revolution flocked to Chesapeake merchant ships may have been bravado, but it contained a kernel of truth. Black sailors such as Philip Johnston found themselves sold by ship captains and shipmates for 'what reasons [they] could not tell.' Although Philip asserted he had been 'born free' he was unable on his own to escape enslavement.

[25] Free black seamen, such as Anthonio Gonsaloes and Francisco Gonsaloes, found themselves subject of white mariners attempts to sell them in the Chesapeake for profit.

[26] Philip’s and the Gonsaloes’ stories were not unusual --- white sailors even financed their return home during war by stealing a ship with Black seamen, selling the Black tars and using the proceeds. In contrast, the Royal Navy may have been 'brutally pragmatic' in its employment of Black seamen, and discriminatory in its pay and promotion practices. It did not, however, countenance the kidnapping and selling of Black mariners.

[27]

Black mariners such as William Stephens were not only commonplace in British American colonies but were critical to both its naval and commercial successes. Moving across the Atlantic they provided both the muscle and maritime expertise necessary to move the military forces and commodities upon which Britain’s imperial might was based. However, throughout the eighteenth century Black tars found themselves at risk of being kidnapped, captured and sold as prize goods or returned to their former slave masters. In the last quarter of the century British naval officers may have taken steps to assist runaways, particularly after the

Somerset decision in 1772 holding that slave owners in England could not coercively force their bondsmen to leave English soil.

[28] And the Navy was instrumental in

Equiano, David King, Prince Prince and scores of other Black sailors reaching England where they were able to live independent lives. However, Naval personnel continued to return ex-slaves to their former owners and treat Black sailors on enemy ships as prize goods.

[29] The result was that for most Black tars, including William Stephens, independent lives as a mariner in the Western Atlantic was fragile.

-----

[2] While slaves in colonies north of Delaware had literacy rates approaching 10%, most North American slaves were illiterate. Antonio Bly, “Pretends he can read”: Runaways and Literacy in Colonial America, 1730–1776,” Early American Studies 6, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 269-271.

[3] The BMD contains 53 fields of data: age, ethnicity, place of birth, ships served on, etc. It includes references from ship musters, court records, fugitive slave advertisements, newspaper dispatches, merchant and governmental records, as well as a wide variety of miscellaneous documents from more than thirty archives across the Atlantic. The database can, as was done in the “Global Seafarers” display in Merseyside Maritime Museum’s recent “Black Salts” exhibit, demonstrate the global movement of black mariners. It also enables historians to detail the lives of individual Black sailors and the employment patterns of such men. See e.g., Michael Bundock, The Fortunes of Francis Barber (New Haven, 2015), 85, 235n14; Charles R. Foy, “Black Seamen at Scarborough, 1748-1756,” https://www.africansinyorkshireproject.com/black-seamen-at-scarborough.html; Charles R. Foy, “Compelled to Row: Blacks on Royal Navy Galleys During the American Revolution,” Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2017/11/compelled-row-blacks-royal-navy-galleys-american-revolution/; Charles R. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” International Maritime History Journal, 28, no. 1 (Feb. 2016): 6-35.

[6] Examples include: Welcome Arnold Papers, John Carter Brown Library, Providence, RI; Aaron Lopez Papers, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY; Henry Laurens Papers, X, 241n; Samuel Gilford Papers, New-York Historical Society, Box 3, Folder 1; Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry (Chapel Hill, 1998), 239; David Barry Geggus, Bondmen & Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Baltimore, 1999), 297n51 .

[7] Joyce Goodfriend, Before the Melting Pot (1992), 124. Not all ship captains were so supportive of runaways. See e.g., Harry Gandy 4 Aug. 1796 Letter, Granville Sharp Papers, D3549/1/G2, Gloucester Records Office (Captain put stowaway to work on his ship, then had the runaway imprisoned in Bristol and subsequently attempted to compel the unfortunate bondman to be returned to his Dominica slave owner).

[9] Charles R. Foy, “Eighteenth-Century Prize Negroes: From Britain to America,” Slavery and Abolition 31:3 (Sept. 2010): 379-393.

[11] HM Galley Scourge, Muster, 1779-1785, TNA ADM 36/10427; HM Galley Arbuthnot, 1783-1786, TNA ADM 36/10426.

[12] See e.g., Maryland Gazette, Apr. 30, 1752, Oct. 29, 1762 and Mar. 10, 1774. As the BMD contains few entries from Chesapeake planters’ or merchants records this number undoubtedly undercounts Chesapeake Black mariners.

[13] See e.g., Maryland Gazette, June 10, 1762, Sept. 20, 1764, May 5, 1768, June 25, 1795 and July 4, 1799.

[14] HM Galley Cornwallis Musters, 1777-1782, TNA ADM 36/10259; Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Nicholson), Richmond, Mar. 3, 1781.

[15] These have been identified from a review of Virginia and Maryland fugitive slave advertisements and a random sampling of Royal Navy musters. While this review understates the number of maritime fugitives it does provide a sense of their not inconsiderable numbers. It is an attempt to provide greater specificity to which slaves fled via the sea and their numbers. As Cassandra Pybus has demonstrated, white Southerners often exaggerated the numbers of slaves fleeing to British forces. Cassandra Pybus, “Jefferson’s Faulty Math: The Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution,” William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol. 62, no. 2 (Apr. 2005), 244-45.

[16] Maryland Gazette, Aug. 3, 1759.

[17] Maryland Gazette, Aug. 12, 1762, Nov. 30, 1763.

[18] Virginia Gazette (Rind), Williamsburg, Oct. 31, 1771; Maryland Gazette, Aug. 2, 1779.

[19] HMS Rose, Muster, 1775 TNA ADM 36/7947; South-Carolina Gazette (Timothy), Oct. 3, 1761.

[20] Morgan, Slave Counterpoint, 254.

[21] See e.g., Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Aug. 1, 1766; Pennsylvania Gazette, Dec. 18, 1766; Virginia Gazette (Nicolson & Prentis), Oct. 25, 1783; Pennsylvania Packet or General Advertiser, Oct. 28, 1783.

[22] Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), Jul. 26, 1762.

[23] See e.g., Philadelphia Gazette & Universal Daily Advertiser, Nov. 6, 1797. One of the few examples of a successful prosecution for employing a maritime fugitive was in 1725 when Captain Moffet was fined for not barring a slave from stowing away on his ship. New England Weekly Journal, April 24, 1724.

[24] For example, between 1766 and 1790 one Saint-Domingue newspaper published more than 200 advertisements regarding maritime fugitives.

[27] Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 9, 899; Norwich Packet, Jan. 23, 1781; Simon Schama, Rough Crossings (London, 2005), 13 and 168; Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” 6-35.

[28] Charles R. Foy, “‘Unkle Somerset’s freedom: liberty in England for black sailors,” Journal for Maritime Research 13:1 (Spring 2011): 21-36.