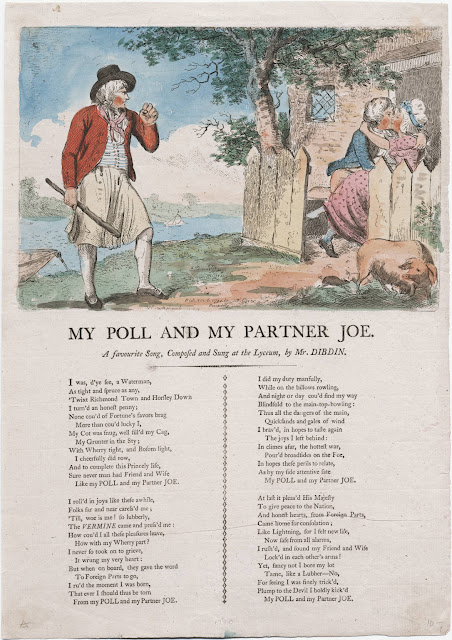

"The Treat at Stepney," artist unknown, 1740-1760,

British Museum.

In her book

London, 1753, Sheila O'Connell relates that Stepney was a rural suburb of London, and boasted "a downmarket version of the pleasure gardens at Vauxhall and Ranelagh." The elites have their galleries and meticulously cultivated gardens, while the common man has Stepney. Stepney is still part of London today, and is only a short distance from the traditionally maritime neighborhood of Wapping.

Along with the engraving of sailors at play on shore, there is a helpful verse that names many of the principal characters, and catalogs their vices:

At Stepney now, with Cakes & Ale, Our Tars their Mistresses regale, What Humour sits on ev'ry Brow, John grows Polite, he knows not how; And marks with meaning grin, below How Frank, who, extended on the Beach, Surveys the Port he hopes to reach; There Kit Admires, with keener taste, The Trollop, whom he weds in haste And jovial James, with lifted Glass, Drinks to and Toasts, his fav'rite Lass, Mean while the Sounde their fidler Scrapes, With fist and Elbow, Richard apes: And equal mirth's, in distant views, Attracks the eyes of Various Crews.

At the left and in the background at those "Various Crews." We only get a good look at one of them, who wears a cocked hat reversed. His jacket sports open slash cuffs, and there is a neckcloth bound around his neck. In his right hand he supports a pipe. The other tars appear to be similarly dressed, one of whom drinks from a punch bowl. Beyond that, there isn't much to say.

We can say more about the fiddler. He wears breeches with a fly front, round toed shoes with rectangular buckles, no waistcoat, and a full length coat with slash cuffs. It is possible the fiddler is no sailor, and merely the entertainment provided by this house of mirth.

Beneath the table is Frank "

who, extended on the Beach, Surveys the Port he hopes to reach." This is innuendo that underlines the obvious fact that Frank is looking up the petticoats of a woman at the table. Frank wears a jacket that ends below the waist, breeches with ribbon fasteners below the knee, no waistcoat, white stockings, and pointed toe shoes. At his feet is a discarded cocked hat and bob wig. I am not sure if the hat and wig belong to Frank or the fiddler.

Kit is oblivious to Frank's "observation" beneath the table, and sidles up to his "

Trollop, whom he weds in haste." As O'Connell states, informal and secret weddings were common enough in the mid-eighteenth century to draw Parliamentary intervention with the

Marriage Age of 1753.

Kit's curly hair runs down to his shoulders, resting on the striped or creased neckcloth that is draped over his jacket. His cuffs, like those of everyone else in this piece, are slashed.

John, the centerpiece of this print, looks as though he has imbibed a bit too much. His cocked hat is a bit ragged and rather small. A dotted neckcloth hangs down over a waistcoat decorated with narrow horizontal stripes. His jacket is long, almost coat length, and featurs unbuttoned slash cuffs with cloth covered buttons. John's breeches are likewise striped, though vertically. At his feet is a broken pipe and a sailor's stick.

At the far end of the table are the two remaining members of their mess. Raising a glass is James, who toasts the woman beside him. He wears a plain neckcloth, single breasted jacket with slit cuffs, and plain breeches.

Near as I can figure, the last character is Richard, who "

With fist and Elbow...apes." I think Richard is trying to mimic the movements of the fiddler across the table. Richard wears a plain neckcloth, long jacket or coat, no waistcoat, breeches fastened by ribbon, and pointed toe shoes with rectangular buckles.