The Banks of the Shannon, published by Bowles & Carver, 1787, reprinted 1799, British Museum.

A colorful print, this Bowles and Carver piece touches on the Sailor's Farewell trope, but with a twist. The young gentleman clasps the hand of his crying sweetheart, but the insistent hand on his shoulder of a naval officer bids him away with the press gang. His lover gives us a tearful poem:

But woe is me the Press gang came and forc'd my Ned away,Among the many things that make this piece interesting is the fact that this is the River Shannon, and so the main figures are Irish. Upon reflection, I cannot think of any other prints, drawings, or paintings that I have examined that explicitly illustrated Irish tars. Scotch, American, and English certainly, but thus far the Irish have escaped notice. It is perhaps the leveling nature of the Wooden World (as NAM Rodger calls it) that makes them invisible to art. The overwhelming majority of images do not give any nationality to sailors. They are all of a kind.

Just when we nam'd next Monday fair to be our Wedding day.

My love he cry'd they force me hence but still my heart is thine

All peace be yours my gentle Pat while War and toil is mine

With riches I'll return to thee, I sob'd out words of thanks

And then we vow'd eternal truth on Shannon's flow'ry Banks.

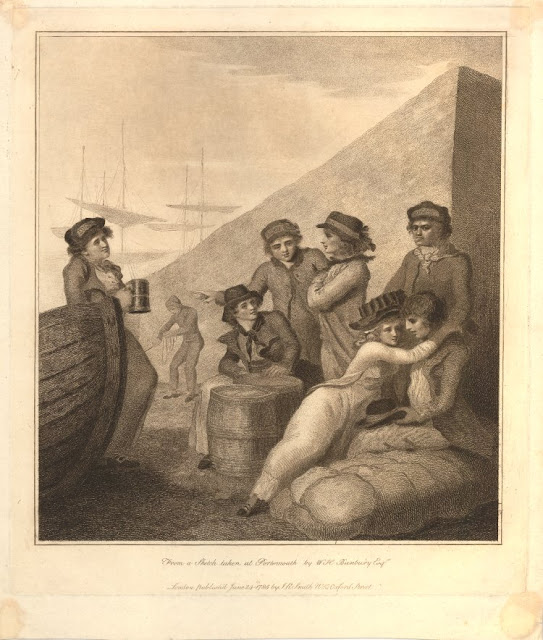

Pat and Ned look clearly distraught, but the press gang seem to be enjoying this tearful parting.

With cudgel in hand, a grinning officer tugs at Ned's shoulder. Behind him are array the men of the press gang, and at least one of them also carries a cudgel.

They are uniformly equipped with black round hats that sport narrow upturned brims and big blue bows. Blue bows on round hats are typical of Bowles' prints. Most of the mariners are hidden behind the officer, but we do get a peek at a pair of white trousers with narrow vertical red stripes over white stockings.

There is one sailor in particular that we get a good look at.

His hair hangs down in brown curls and appear to just barely drape over the black silk neckcloth over his blue jacket with its slit cuffs. A red double breasted waistcoat with white metal buttons hangs above his plain white slops/petticoat trousers. The shading indicates that this waistcoat is not tucked in, and is cut off at the natural waist. He wears white stockings and pointed toe shoes.