|

| Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, John Greenwood, c. 1752-1758, Saint Louis Art Museum. |

Hear me out.

I love shanties. Back when I worked at the Maritime Museum of San Diego, I spent many a weekend singing from the bow of the Surprise and the poop of the Star of India, and attended more than my fair share of their Sea Chantey Festivals. Go to the next one on August 26, you won't regret it.

But we also have to understand that the eighteenth century is not the nineteenth, and that not all maritime traditions are as immemorial as we think they are.

There are many definitions and spellings of the term 'shanties.' Richard Runciman Terry gives a fairly narrow definition in his The Shanty Book:

Shanties were labour songs sung by sailors of the merchant service only while at work, and never by way of recreation.[1]William Main Doerflinger in his 1990 Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman gives a more generous definition that allows for the inclusion of naval seamen and the use of shanties for recreation:

Shanties are the work songs of the sailor of square-rigger days.[2]Gibb Schreffler is among the few academics to take a scholarly approach to the study of sea shanties. Earlier this year he published Boxing the Compass: A Century and a Half of Discourse About Sailor's Chanties, examining the discussions of and approaches to studying shanties. On a recent episode of the podcast Backstory Radio, Schreffler gave a much more specific and compelling definition of shanties:

Shanties are always call and response songs. They always have a leader and a chorus. The chorus is performed by all of the crew aside from the leader, and the leader performs as a soloist. And what this means is that the chorus is a fixed part of the song. All of the crew must know that part of the song, so that they can come in and sing it together. However, what the leader or the caller sings is completely optional to his whim, and therefore it’s typically improvised.[3]While Schreffler's is probably the best definition, all these definitions have in common is the use of shanties to coordinate work at sea.

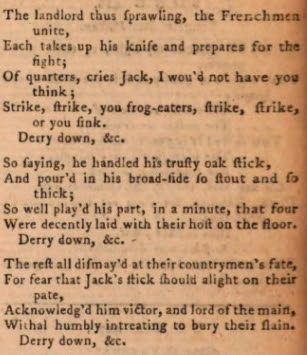

All of the surviving eighteenth century songs that I've examined (and sung) are of forms typical of the era at large and not a maritime working context specifically. Period songs with a maritime theme are often based on existing tunes that are not explicitly work songs. As George Carey pointed out in his introduction to A Sailor's Songbag, a transcription of fifty-seven songs collected by an American sailor in the 1770's, only six 'deal with the sea, a fact that dispels the sometimes stereotyped notion that sailors only sang about their profession.'[4] Further, no sailor of the eighteenth century writes of work songs, much less those with a call and response format. Stan Hughill in his 1961 Shanties from the Seven Seas makes mention of the lack of sources referring to shanties as such in the eighteenth century.[5] Doerflinger, in his Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman, argues that shanties go much further back, but fell into 'comparative disuse during the wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.'[6] Paul Gilje, in his very entertaining To Swear Like a Sailor, also states that 'few commentators mentioned shanties until the 1830s. By then they seem to have become widespread.'[7]

I do not argue that there was no singing on the ship. Samuel Kelly suggests there was a time and a place for music in relating a humorous anecdote in which an army band took up their instruments at an inopportune time aboard a transport in 1783:

At daylight the [regimental] band assembled to play a tune on the quarter-deck (I imagine from custom, or regimental orders), this aroused the fury of our master (who probably had not yet forgotten the danger of the night, and being still near the rocks), was astonished at this inconsideration. He therefore with the speaking trumpet in his hand began to lay it on the heads of the musicians with great violence, which soon dispersed the harmony.[8]Of course, those were not sailors, they were using instruments rather than their voice alone, and they violated the officer's domain of the quarter deck. Seamen were probably more attune to the appropriate time for singing.

Christopher Hawkins, many decades later, remembered crewing an American privateer schooner as she chased down a fat British brig in 1777:

The second Lieut. took the helm and seemed in command-ordered the boatswain after trimming the sails and the great part of the crew to be seated aft and attend to the singing of some of the crew, (Capt. of Marines).[9]When Hawkins' crew was later captured by the Royal Navy, they defied the British in song:

Our crew were full of vigour and entertained the crew of the frigate with a number of our patriotic songs. Although entertained the loyalists were by no means pleased. The singing was excellent and its volume was extensive-and yet extremely harsh to the taste of the captors. The guard frequently threatened to fire upon us if the singing was not dispensed with, but their threats availed them not. They only brought forth higher notes and vociferous defiance from the crew. The poetry of which the songs were many of them composed, was of the most cutting sarcasm upon the British and their unhallowed cause. I recollect the last words of each stanza in one song were," For America and all her sons forever will shine." In these words it seemed to me that all the prisoners united their voices to the highest key, for the harmony produced by the union of two hundred voices must have grated upon the ears of our humane captors in a manner less acceptable than the thunder of heaven. For at the interval of time between the singing of ever song the sentinels would threaten to fire upon us and the officers of the frigate would also admonish with angry words. "Fire and be damn'd" would be the response from perhaps an hundred voices at the same instance. The singing would again be renewed and louder if possible. In this manner the first night was spent.[10]Hawkins is prone to exaggeration, and this anecdote does give me pause, but music was certainly present in the population of American seamen captured by the British during the Revolutionary War. As mentioned above, Timothy Connor, held at Forton Prison from 1777 through 1779, kept a collection of songs numbering fifty seven in all.[11]

British mariners were also fond of music. When John Nicol visited Hawaii in 1785, one of his shipmates earned a place of respect through his singing:

We had a merry facetious fellow on board called Dickson. He sung pretty well. He squinted and the natives mimicked him. Abenoue, King of Atooi, could cock his eye like Dickson better than any of his subjects. Abenoue called him Billicany, from his often singing 'Rule Britannia'. Abenoue learned the air and the words as near as he could pronounce them. It was an amusing thing to hear the king and Dickson sing. Abenoue loved him better than any man in the ship, and always embraced him every time they met on shore or in the ship, and began to sing, 'Tule Billicany, Billicany Tule,' etc.[12]There is a difference between songs, shanties, and chants. When it came to working tunes, chants appear to have been the choice.

Ebenezer Fox, a young man who served aboard a privateer and was held aboard the prison ship Jersey during the Revolution, referred to work chants in his memoirs. He wrote of the sailors using 'yo-hoi-ho heave' in tossing a young sailor into the water for a swim, and in specifically referencing use of the windlass 'We then weighed anchor, for the last time, with a joyful "Yeo-a-hoi," and set sail for our native land.'[13]

Fox's memoir must be read critically, as he was writing many decades after the event, and there are inconsistencies in his text. The latter quote, however, falls in line with another primary source.

William Falconer's 1769 An Universal Dictionary of the Marine was a seminal work, and though he does include fanciful fabrications, his book is very helpful. In Falconer's entry on 'Windlass' (an identical entry in his 1780 edition is included below) he writes that when sailors are using handspikes in the device to weigh anchor, 'the sailors must all rise once upon the windlass, and, fixing their bars therein, give a sudden jerk at the same instant, in which movement they are regulated by a sort of song or howl produced by one of their number.' Taken with Fox's account of weighing anchor, these sources corroborate each other.

|

| William Falconer, An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, The Strand (London) T. Caddell, 1780, page 338, University of California Libraries via Internet Archive. |

| William Falconer, An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, London: T. Caddell, 1769, page 491, Library of the Marine Corps via Internet Archive. |

The closest we might come is an anecdote related by the American Reverend Ammi Robbins, who experienced that familiar frustration of not being able to get a song out of his head:

The boatmen sing a very pretty air to 'Row the boat, row' which ran in my head when half asleep, nor could I put it entirely out of mind amid all our gloom and terror, with the water up to my knees as I lay in the boat. My difficulty was one passage I could not get.[14]

It is not positively a shanty, but Reverend Robbins does say there was 'one passage I could not get,' which implies different passages broken up by the short chorus of 'row the boat, row.'

Reverend Robbins alone gives us evidence of what we might think of as shanties. It is widely agreed that there was a strong African influence on the creation of shanties, particularly by the enslaved people of the New World, and the permeation of their influence took time. As I quoted Gilje earlier, shanties really took hold in the 1830's. Schreffler explains why:

Reverend Robbins alone gives us evidence of what we might think of as shanties. It is widely agreed that there was a strong African influence on the creation of shanties, particularly by the enslaved people of the New World, and the permeation of their influence took time. As I quoted Gilje earlier, shanties really took hold in the 1830's. Schreffler explains why:

The development of the shanty genre was happening at precisely the same time as the blackface minstrel genre of music was developing in the United States. We know that the minstrel music was at that time the middle of the 19th century I’m talking about. Kind of starting in the 1830's, having its first peak actually in a year. We can pinpoint 1843 and then continuing from there the minstrel genre was the most popular genre of music in the United States, and eventually spread globally. And this would have been popular music with all of the sailors. Whether the sailors were white or black, they were interested in this type of music. It was the popular music.[15]There has also been some projecting backward, which is very common in the study of maritime history. A belief has run throughout history that sailors don't really change. Whether it is in their religious beliefs, language, or dress, people then and now often imagine sailors are slow to change, and that traditions of the sea are immemorial. As such, ballads and songs that existed at the time are cast as sea shanties when that was not their intention.

Sailors did sing. When we use the term 'shanties,' we imply a specific musical tradition of work songs that was not yet fully formed in the Atlantic world.

---

[1] Terry, Richard Runciman, The Shanty Book: Sailor Shanties with Lyrics and Music, ebook: CreateSpace, 2014, page 10

[2] Doerflinger, William Main, Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman, revised edition, Glenwood, Illinois: Meyerbooks, 1990, page 1.

[3] Schreffler, Gibb, "Songs of the Sea," BackStory Radio, "Thar She Blows Again," October 12, 2018, transcription, accessed October 19, 2018, <https://www.backstoryradio.org/shows/thar-she-blows-again/>.

[4] Timothy Connor, A Sailor's Songbag: An American Rebel in an English Prison, 1777-1779, George C. Carey ed., Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1976, page 16.

[5] Hughill, Stan, ed., Shanties From the Seven Seas: Shipboard Work-songs and Songs Used as Work-songs from the Great Days of Sail, London: Routledge & Kegen Paul, 1961, page 5.

[6] Doerflinger, Songs of the Sailor, page xiv.

[7] Gilje, Paul A., To Swear Like a Sailor: Maritime Culture in America, 1750-1850, New York: Cambridge University, 2016, page 170.

[8] Kelly, Samuel, Samuel Kelly: An Eighteenth Century Seaman, Whose Days Have Been Few and Evil, edited by Crosbie Garstin, Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1925, page 78.

[9] Hawkins, Christopher, The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins, edited by Charles I. Bushnell, New York: Privately Printed, 1864, page 14.

[10] Ibid., pages 63-64.

[11] A Sailor's Songbag.

[12] Nicol, John, The Life and Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner, edited by Tim Flannery, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997, page 83.

[13] Fox, Ebenezer, The Adventures of Ebenezer Fox in the Revolutionary War, Boston: Charles Fox, 1847, pages 190 and 224.

[14] Robbins, Rev. Ammi R., Journal of the Rev. Ammi R. Robbins: A Chaplain in the American Army, in the Northern Campaign of 1776, New Haven: B.L. Hamlen, 1850, page 18, Library of Congress via the Internet Archive.

[15] "That She Blows Again," Backstory Radio, <https://www.backstoryradio.org/shows/thar-she-blows-again/>.